The decision to stick with the bags fly free® policy paid dividends when Southwest attracted new Customers from competitors.

The Way Things Were: A Texas-Sized Flashback

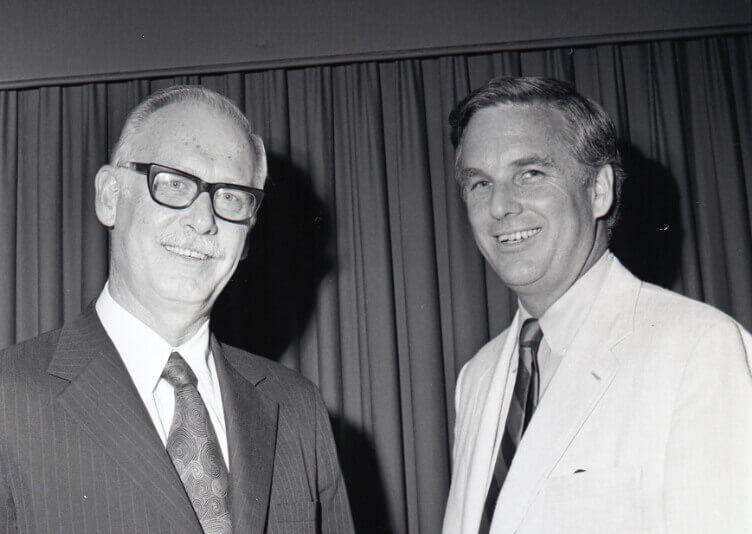

The Braniff pilots knew their business was in trouble the moment the door to the Cockpit Bar in Dallas swung open and Lamar Muse and Rollin King strode in. The two Leaders of the upstart airline that was causing such a headache over at Braniff bypassed the bar and joined a group of Southwest Airlines regulars: post-shift Dispatchers, Ramp Agents, and Mechanics.

“The Braniff pilots practically dropped their beers on the table,” said Dan, a Southwest Dispatcher at the time. “‘Holy cow, we haven’t got a chance,’ was written all over their faces.”

Executives taking the time to build relationships with Employees over a beer? Talking to Pilots about what Customers were saying, and asking for input about how to improve service? That focus on People was going to give Southwest a competitive edge as it built its business. In fact, connecting with Frontline Employees was a special priority for King, a certified Pilot who flew 25 to 30 hours a month just for the opportunity to observe the airline in action.

It was the 1970s, and Southwest was already busy turning the airline industry upside down with its unconventional approach to pretty much everything—from outfitting its Hostesses, as they were known, in hot pants and go-go boots to modeling its aircraft turnaround strategy after professional racing pit crews.

Former Southwest President Lamar Muse, left, and Southwest Founder Rollin King.

For the Southwest Maintenance operation, the early years involved a lot of creative problem solving. Parts and tools were often in short supply. Mechanics would call up their friends at other carriers, who risked the wrath of their managers to loan Southwest the parts it needed—either out of pity, or because they never considered Southwest a serious competitor.

Reservations Agents were the first point of contact for Southwest Customers and played an increasingly critical role as Southwest added new cities to its schedule. By 1973, demand had grown, thanks to the $13 Fare War and quite a few bottles of scotch, and Southwest established the original Dallas Reservations Center (DRC).

Like their counterparts at the airport, Reservations Agents became adept at working with what they had. The only technology they had from the start was the multi-line rotary telephone. Everything else was low-tech: Chalkboards displayed flight and fare information, and agents checked off seats on a chart as they were sold. When all the seats were crossed off, they stopped selling tickets. Prepaid Customer tickets were recorded on index cards and counted by hand. Flight manifests were created at the gate when each Customer spoke their name into an audio cassette recorder. After the flight landed safely, the Ticket Agent, as they were called, would reuse the tape for another flight.

A Reservations Agent at work in the 1970s.

By 1980, manual reservations had been replaced by the Company’s first foray into computerized reservations, using Bunker Ramo computers. Processing a million Customers a year meant the Company needed even more Reservations Agents. With the DRC at maximum capacity, Southwest opened a second Reservations Center in San Antonio.

Southwest continued to lead the industry in reservation innovations over the coming decades, as the first major carrier to offer Ticketless Travel, the first airline to launch a website, and the first to sell seats online. In 2017, Southwest completed the single largest technology initiative in its history when it implemented a $250 million integrated reservation system.

Behind every modern innovation is the Southwest legacy of doing things differently—a legacy that began in the 1970s when Executives shared beers with ground crews after hours; resource-strapped Employees solved problems with what they had on hand; and phrases like, “we can’t do it,” or “it’s not my job” weren’t part of the Southwest vocabulary.