Fare Play: $13 Bottles of Booze and The Two-Tier Fare System

On an otherwise ordinary morning in February 1973, Southwest President Lamar Muse was paging through one of the local Texas papers. And that’s when he saw it: a full-page ad from Braniff Airlines, a particularly bitter rival that had previously waged a prolonged legal fight to keep Southwest from taking flight.

The ad announced the launch of what Braniff called a “Get Acquainted” sale. It offered cut-rate $13 fares on its Dallas to Houston route, which happened to be one of the few routes Southwest was flying.

An initial reaction of incredulity—how in the world could an airline that’s been around for 40 years have the gall to launch a “get acquainted” sale?—turned into a need to throw a counterpunch. Lamar knew $13 fares were far below Southwest’s break-even point, making it a clear threat to the upstart airline’s survival. If Southwest didn’t find a way to counter this push, it was headed for a one-way trip to bankruptcy.

He picked up a pencil and started scrawling down a passionate response, which he planned to turn into an ad. Unfortunately, the initial draft was a little too heated.

Both Herb and Lamar knew why Braniff was targeting Southwest. The previous year, Southwest had experimented with a radical innovation, which would later be called one of the most Customer-friendly innovations in airline history: The Southwest two-tier fare structure.

The structure offered travelers the option of choosing between two different fares: a regularly priced Executive Class and a half-price Pleasure Class ticket during weekends and on flights departing after 6:59 p.m.

Prior to this move, old guard airlines had assumed there were only two types of travelers in the world: Those who could afford to fly, and those who should stick to trains, buses, and cars. The established players did not see the utility of introducing alternative fares, as they suspected lower-priced fares would simply reduce their profits.

Southwest took a more democratic approach, believing that more “elastic” fares would encourage more Americans to fly. Potential Customers quickly showed their appreciation. Before the move, Southwest averaged 17 Customers per flight; by February 1973, it was averaging 75.

As Herb read over Lamar’s ad, however, he searched for ways to soften its tone. Herb—who would later compare this stretch of Company history to being in the Foreign Legion: “(We) had a firefight every two days”—certainly agreed with Lamar that it was time to make war not love. But as he discussed the edits with Lamar and Southwest’s ad agency, the conversation turned back to the idea of giving Customers a choice, which had proved so powerful in its two-tier ad push.

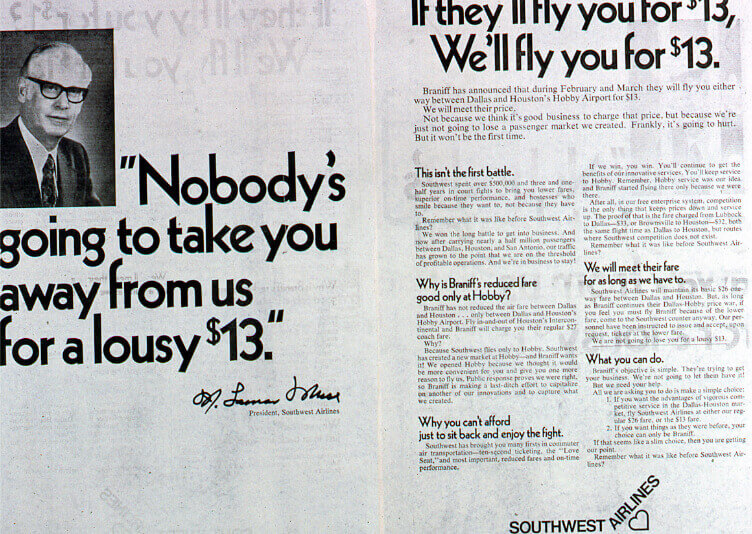

Eventually, a balance was struck. Along with a giant headshot of Lamar Muse, the new ad would feature the catchy tagline: Nobody’s Going to Shoot Southwest Airlines Out of the Sky for a Lousy $13.”

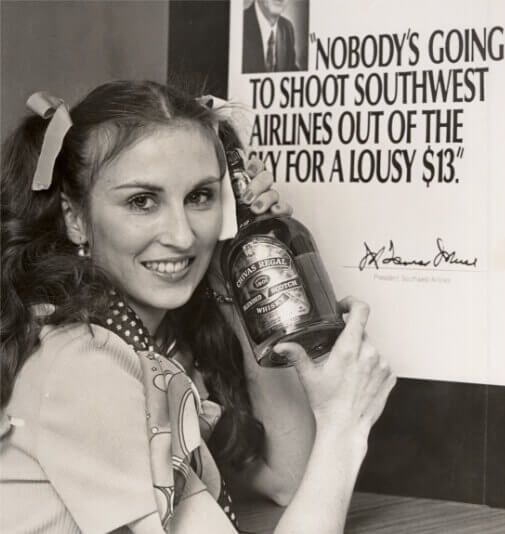

Then-Ticket Agent Georgeann Harris poses with a bottle of Chivas Regal and the eye-catching Southwest advertisement.

It was the offer embedded in the body text of the ad, however, that caught everyone’s attention. Southwest was willing to match Braniff’s fare price, allowing Customers to buy a Southwest ticket for just 13 bucks. Or they could buy a full-price $26 ticket and receive their choice of a gift worth $13: either a fifth of liquor or a leather ice bucket.

While a fifth of liquor was unlikely to retail for $13 at the time, Southwest calculated that its primary Customers—short-haul business travelers—were likely to expense their $26 tickets and pocket the booze for themselves.

The ad struck a deep and immediate chord with the general public, turning the plucky young airline into an immediate favorite within some business communities in Texas. Soon crowds began showing up at Southwest gates in Dallas, San Antonio, and Houston, wondering why this crazy airline was handing out enough bottles of booze to stock every bar in the great state of Texas.

Southwest’s advertisement was a full-page declaration of war against Braniff’s fare cut.

Much to the relief of the top brass at Southwest, three-quarters of Southwest Customers opted for the $26 free-gift option. Business travelers loved the promotion so much that Southwest received hundreds of letters praising the deal.

Now Braniff was the one fuming. At one point, Herb received a call from the Texas Alcohol Beverage Commission, which said it was receiving complaints from teetotalers over the sheer volume of booze Southwest was giving away.

Herb saw through that complaint immediately. “I suspect,” he said, “that the complaining organization begins with a ‘B’ that doesn’t stand for ‘Baptist.’” The caller—realizing Herb had deduced that Braniff was behind the campaign—could do little but sheepishly hang up the phone.

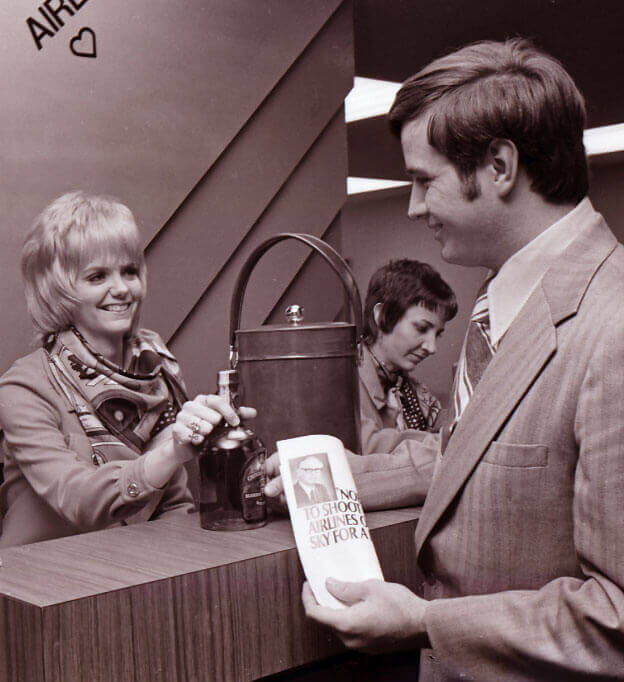

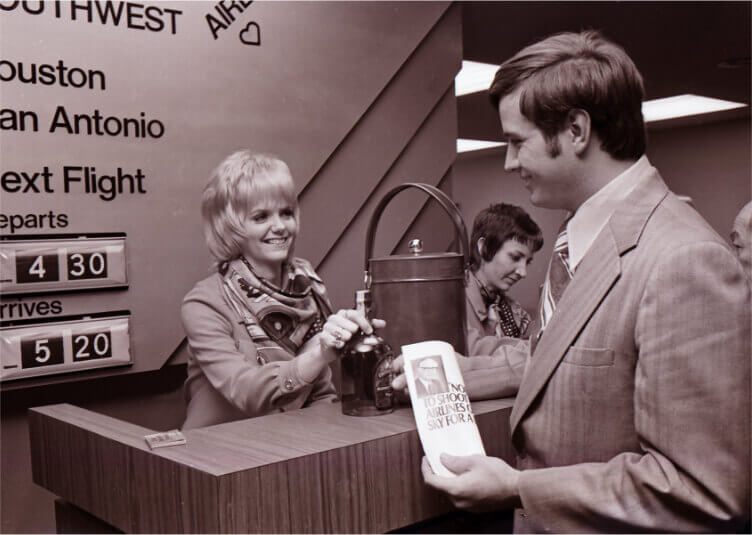

A happy Southwest Customer holds the famous advertisement and receives his bottle of liquor.

From that moment on, the fates of Southwest and Braniff peeled off in opposite directions. Braniff would cease operations in 1982 before making an unsuccessful comeback bid in in the early 1990s.

By contrast, Southwest— with its “love potion” cocktails, cheery Hostesses, and free peanuts—turned its first profit at the end of 1973. And it never looked back, remaining profitable for 47 consecutive years through 2019. Although a litany of other fare wars, far beyond Texas, would follow, the essential truth of that early ad remains undisputed: No one has—or ever will—shoot Southwest out of the skies.