Herb Kelleher

Courting Success: Early Southwest Legal Battles

In the summer of 1968, a high-stakes legal drama broke out in an Austin state district court. It was the courtroom equivalent of a barroom brawl. Tempers flared, insults were thrown like right hooks, and there was high drama at every turn.

At issue was whether a new airline—hoping to offer Texans an expanded menu of low-fare intrastate flights between San Antonio, Dallas, and Houston—had the right to compete with entrenched industry powers.

The legal skirmish pitted Herb Kelleher, representing upstart Air Southwest, against lawyers from Braniff, Trans-Texas Airways, and Continental Airlines. The opposing lawyers argued these three Texas cities were sufficiently served by interstate carriers and couldn’t support the entry of a new carrier.

The distinction between interstate airlines (which served cities in multiple states) and intrastate carriers (which only operated in a single state) was key to the proceedings. At the time, the airline industry was far more regulated than it is today. Essentially, the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) wielded absolute control over the launch of new interstate carriers, as its approvals and certifications were required to initiate service. In addition, the CAB possessed incredible control over the fare prices interstate airlines charged and the routes they flew.

Herb and Rollin King, however, had already identified a loophole. If Southwest limited its flights to Texas, it could remain beyond the reach of the CAB and seek certification at the state level.

In February 1968, the Texas Aeronautics Commission unanimously granted Southwest the right to fly between San Antonio, Dallas, and Houston. But before the operating certificate could be formally issued, Braniff, Trans-Texas, and Continental obtained a restraining order.

What followed was the first of many legal battles waged by Southwest to provide travelers expanded flight options and lower fares.

Instead of an opening gavel, the judge could’ve rung a boxing bell. Things became so heated so fast that the Texas Transportation Report called the proceedings the best show in town.

When the verdict finally arrived, Herb’s stomach did a somersault of its own. The injunction held. Round one went to the Goliaths. Then Southwest suffered a second setback when Herb lost his appeal in State District Court on March 12, 1969.

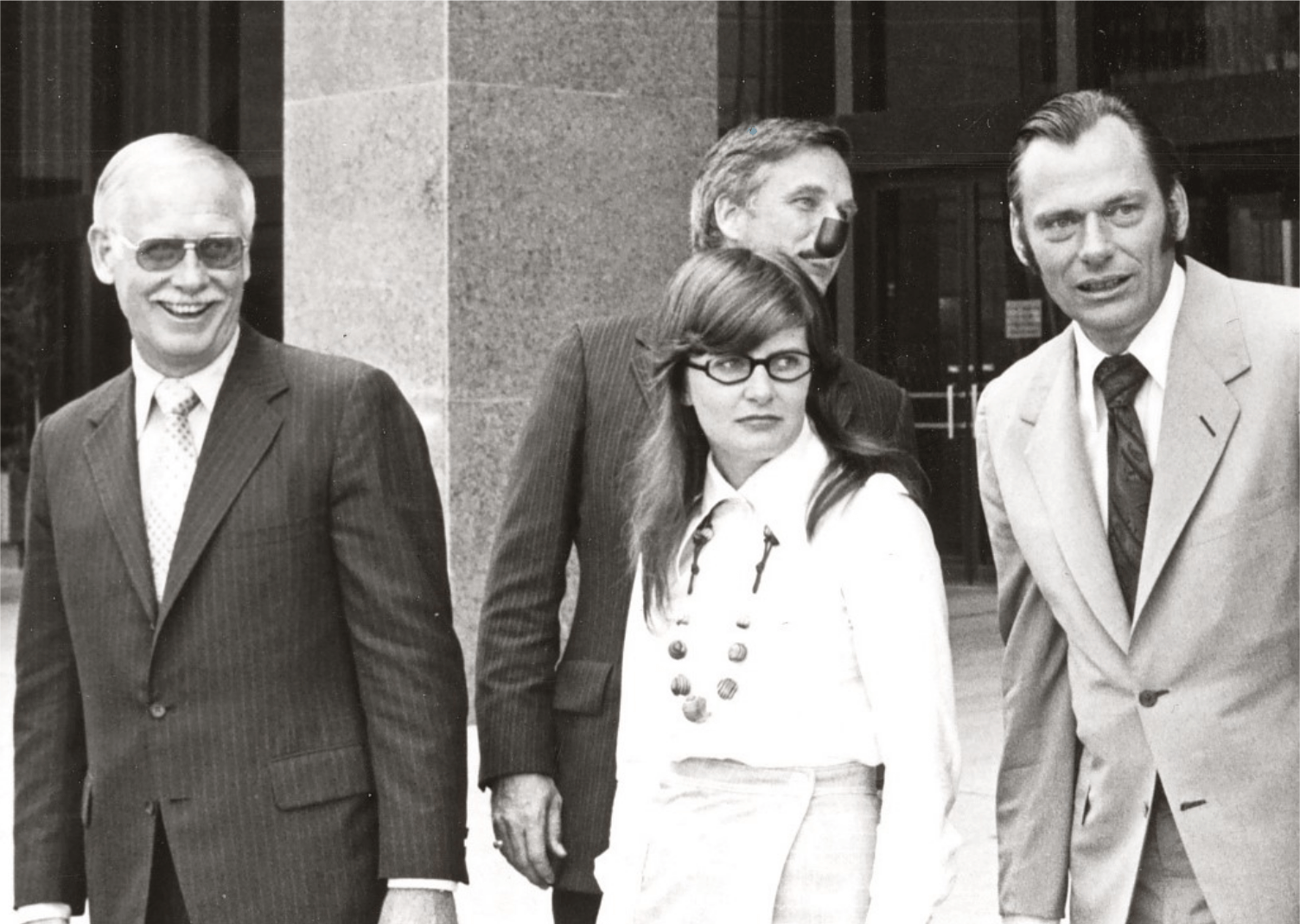

Left to right: Lamar Muse, Rollin King, Colleen Barrett, and Herb Kelleher

Behind the scenes, the Southwest board was losing faith and leaning toward dissolving the Company. Herb became the most vocal dissenter. During one particularly somber meeting, he rose from his chair, surveyed the room, and said, “Gentleman, let’s go one more round with them.” Then, he threw in a much-needed sweetener: He’d pay the legal expenses out of his own pocket. In that moment, the foundations of the Southwest Warrior Spirit were born.

Herb prepared for the next round, this time before the Texas Supreme Court. The real value of a law degree, he would later say, was not the degree itself but what the degree was used to achieve. Throughout his career, he showed little patience for lawyers who wasted time explaining why they couldn’t achieve a particular end. In his mind, “The best lawyers are those that help you to do anything you want to do, by rearranging—within legal, ethical, and moral bounds—any obstacles to the outcome you seek.”

It was becoming clear to Herb that he’d found more than just a business worth fighting for. He’d found a philosophy worth championing. The image he’d later use to describe his fellow Southwest Employees was a merry band of “freedom fighters.”

The Texas Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Southwest’s favor on May 13, 1970. Braniff and Texas International—the new name adopted by the Company’s old foe, Trans-Texas Airways—tried appealing the ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court that same December, but their appeal was denied.

The court victory enabled the airline to raise more money and hire a man who Herb called a “cantankerous genius”, M. Lamar Muse, to serve as Southwest President in 1971. Muse secured the financing for three Boeing 737-200s and prepped flight operations.

Braniff and Texas International didn’t give up. Two days before the scheduled Southwest inaugural flight, the rivals won an injunction from an Austin judge that grounded Southwest.

Herb sprang into action. He hopped aboard one of Southwest 737s, which were making dry runs without any Customers, and told the Pilot to drop him off in Austin on the way to San Antonio.

Once on the ground in Austin, Herb taxied straight to a favorite “watering hole” of several Texas Supreme Court justices. There he found the judge who’d written a 1970 opinion in Southwest favor. The judge promised Herb that he would get his day in court.

Herb still had to persuade the full Texas Supreme Court to overrule the trial court. Even more difficult: persuading the justices that the court had the authority to hold the hearing on his motion in the first place. He quickly phoned Muse to make sure that the Southwest inaugural flight took off the next day. Muse was nervous. He asked what he should do if a local sheriff showed up and prevented takeoff.

“Lamar,” Herb said, “You roll right over that son of a bitch. Leave our tire tracks on his uniform if necessary.”

On June 18, 1971, three Southwest jets—each charging $20 one-way fares—lifted off the tarmac for the first time, shuttling Customers between Dallas, San Antonio, and Houston.

Herb later said, “I think my greatest moment in business was when the first Southwest airplane arrived after four years of litigation, and I walked up to it, and I kissed that baby on the lips and I cried.” It felt to Herb, no doubt, like his first taste of real freedom—both for Southwest and the flying public at large.