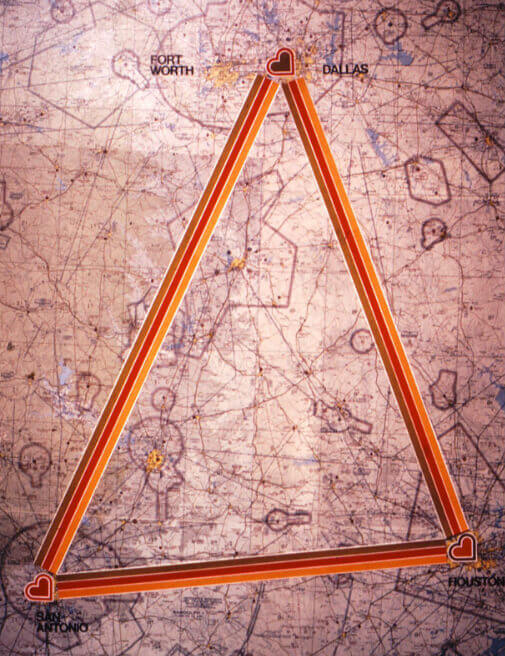

Dallas Love Field, ca. 1970s.

The Wright Amendment Cometh

“If a three-aircraft airline can bankrupt an 18,000-acre, 9-miles-long airport, then that airport probably should not have been built in the first place,” Southwest Founder Herb Kelleher told the judge.

No sooner had the Texas Supreme Court granted Southwest the right to fly in 1971, than Herb found himself once again defending the airline in court. This time, the cities of Dallas and Fort Worth were trying to force Southwest to shutter its operations at Love Field and move to the soon-to-open Dallas-Fort Worth Regional Airport (DFW), 30 minutes outside the city.

The new airport had been a massive undertaking, constructed on a piece of land larger than the island of Manhattan, and city and airport officials were counting on a 1968 bond ordinance to foot the bill. The ordinance required the airlines serving Dallas and Fort Worth from Love Field and several smaller airports to move to the new facility when it opened in 1974, and help fund it through landing and space rental fees.

But in 1968, when the bond ordinance was written, Southwest was barely more than a sketch on a cocktail napkin. The airline hadn’t agreed to the bond—it hadn’t even begun operations when it was set—and felt no obligation to abide by it. Moving to DFW made no sense for Southwest. Love Field’s location, 10 minutes from downtown Dallas, was one of the reasons short-haul Customers chose to fly with Southwest: It provided easy access in and out of the city.

1971-72 route map

In 1972, Southwest told DFW: Thanks, but no thanks. We’ll stay where we are.

Officials at DFW were livid. And so were the airlines bound by the ordinance who were still scrambling to make up for Southwest’s low-fare effect in the Houston market. Lawsuits were levied. The city of Dallas took things even further, making it a crime for a commercial aircraft to operate out of Love Field. And Southwest found itself back in a courtroom in March 1973.

After 32 days in court, a federal judge ruled in Southwest’s favor: The airline could stay at Love Field. Appeals swiftly followed, and in 1977, Southwest prevailed again when the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the lower court’s 1973 ruling. And in a final blow to DFW, the U.S. Supreme Court ended the matter in 1977 when it refused to hear further arguments in the case.

It finally seemed like Southwest could turn its full attention to building its business rather than defending it.

But the Airline Deregulation Act, passed in 1978, renewed tensions between Southwest and DFW. With the government no longer dictating fares and destinations, the airline industry turned into the Wild West, with companies rushing to claim or protect routes, competition driving fares down, and people purchasing tickets in record numbers to enjoy the newfound freedom of unrestricted travel.

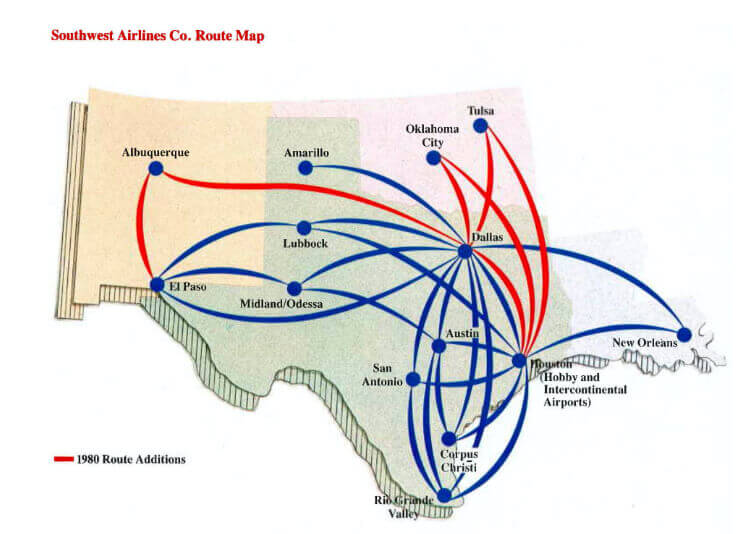

1980 route map

Southwest didn’t waste any time in applying for authorization to open routes outside of Texas and was flying its first interstate route between Houston and New Orleans in January 1979. Venturing beyond the Texas border made Southwest the target of another slew of lawsuits from DFW supporters challenging the Company’s potential expansion from Love Field. Finally, after exhausting their legal recourse with no success, DFW turned to a powerful ally in Congress: U.S. Rep. Jim Wright, the House majority leader.

In a single day, Wright persuaded the House to approve an amendment to the Air Transportation Competition Act of 1979 that would ban all interstate service in and out of Love Field. Wright’s goal was to keep airlines that served DFW from losing business. But months of lobbying by Southwest led to a compromise that allowed nonstop ticketed service between Love Field and four neighboring states: Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico.

Herb thought the Wright Amendment, as it came to be known, was an unfair restriction on the business, but he knew when it was time to move on. “The Wright Amendment is an unjustified pain in the neck,” he said. “But not every legislative pain in the neck amounts to a constitutional infringement.”

Southwest focused on turning an obstacle into an opportunity—focusing on serving cities beyond Texas’ four bordering states with flights originating in cities such as Houston and San Antonio, which were not regulated by the Wright Amendment. The airline heard from its Customers, who remained committed to flying with Southwest despite the inconvenience and indicated they were willing to take extra steps to link their own routes from Dallas by flying to a Wright zone city and then booking a second flight to other destinations Southwest serviced.

Southwest remained what Herb would call “passionately neutral” about the Wright Amendment for the next 25 years. But with short-haul traffic at Love Field declining following 9/11, and other airlines moving their hubs out of DFW, Southwest saw an opportunity to rethink that position. In 2004, the airline announced its intent to fight for a repeal of the Wright Amendment, sparking a nationwide movement to prove that Wright . . . was wrong.