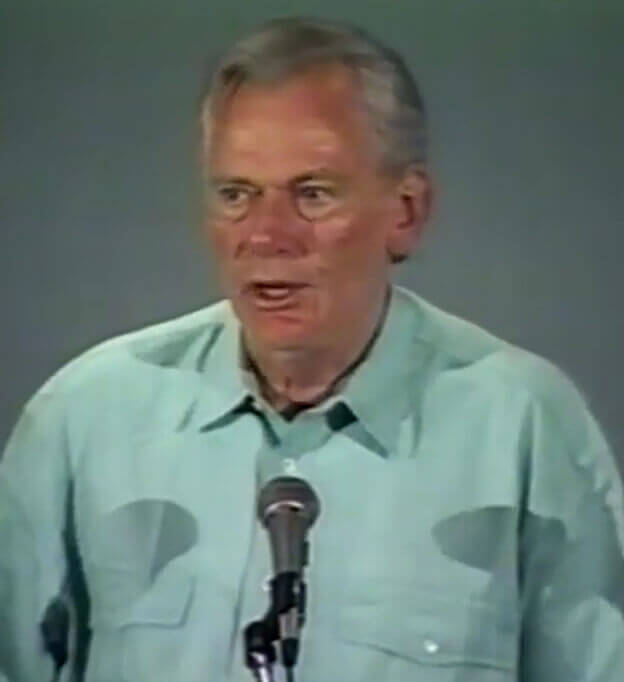

Striking an uncharacteristically grave tone, Herb warns Southwest Employees of the threat posed by United Shuttle.

The Golden State Showdown: United Shuttle vs. Southwest

Herb Kelleher had no intention of soft-peddling this particular threat. Normally when the then-President & CEO addressed his Employees, he made sure to sprinkle in a healthy dose of humor—a self-effacing quip here, a chuckle-worthy anecdote there—to keep the mood light.

Not so in the fall of 1994. Difficult days, he surmised, were coming. He’d decided to be as transparent and direct as possible by taping a speech for the Company’s “video magazine,” which at the time was called As the Planes Turn.

There was, Herb sternly declared, a “war machine” headed Southwest’s way. Its name was Shuttle by United, and it represented “the gravest potential threat to all of the People of Southwest since our very earliest days of operation.”

This new “airline within an airline” had been created with one purpose—and one purpose only—to directly compete with Southwest, especially in the state of California.

At the time, roughly half of the intrastate market in California belonged to Southwest, thanks in part to recent growth at key airports. For example, the Los Angeles Times reported in an August 1994 article that United’s market share at Burbank Airport, which was known as Bob Hope Airport at the time, had been 25 percent in 1991 but had shrunk to just 14 percent, while Southwest’s had risen to 65 percent, according to airport officials.

Shuttle by United would operate as a low-fare, high-frequency, quick-turn carrier, flying many of Southwest’s most popular routes. Although the competitor added a few features—a first-class section, assigned seats, and a window-first boarding policy—it was undoubtedly modeled after Southwest, right down to the snacks and soft drinks served during flights.

This strategy soon became popular with other Southwest competitors. Continental had launched its own subsidiary carrier called CalLite in the fall of 1993. But from Herb’s perspective, Shuttle by United posed the real threat, calling it “an intercontinental ballistic missile targeted directly—and targeted precisely—at Southwest Airlines and at no other carrier in the world.”

This war could be won, he insisted, not by drawing swords but by generating smiles. It would be won by doubling-down on what Southwest did best: maintaining a sterling on-time record, caring for every single piece of luggage as if it was its own, and winning over the hearts of Customers with its unique blend of warmth, humor, and airborne Hospitality.

Herb’s temporary transformation from merry prankster to the living embodiment of a stern four-star general achieved its intended effect. His speech—and an equally inspiring note addressed to all Employees, titled “Commencement of Hostilities”—immediately boosted the esprit de corps of the Company.

As Southwest Employees geared up to launch their charm offensive, its Leadership initiated an important competitive move. Even before the United Shuttle’s scheduled launched on October 1, 1994, Southwest had begun cutting some of its California-based fares by 50 percent, while simultaneously boosting its flight frequency for select routes. These tactics artfully diverted valuable media attention away from the Shuttle’s launch, while underscoring the true low-cost airline in California.

On August 11, 1995, Southwest unveiled California One, a stunning tribute to its commitment to the Golden State.

This was critical, as one of the key questions in this simmering war was how lean and efficient the competition could become and still turn a profit. Profitability, then as now, was dependent upon a metric called “cost per available seat mile” (CASM), which essentially tracks the cost of flying one passenger a single mile.

At the time, Southwest averaged just 7.25 cents per available seat mile, while United averaged 8.5 cents.

Southwest’s overall battle plan? Keep making profits on its low fares while the competition sustained such heavy losses that it would be forced to raise the white flag.

Initially, early returns showed Southwest was in for a protracted fight, as it temporarily lost about 10 percent of its business in some markets. But that proved merely a blip, thanks to the one great differentiator that none of its competitors could match: The Warrior Spirit of its People.

Southwest Employees had been hired and trained for just such a challenge. Existential threats had been a hallmark of its early years. The importance of Teamwork—buoyed by the practical benefits of its strong ProfitSharing Plan—had been engrained in the very fiber of the Company.

If a particular aspect of its operation—in this case, California—was threatened, its People viewed it as a threat to each of them individually.

By the spring of 1996, this “all-for-one, one-for all” spirit helped the Company first regain what market share had been lost in California and then expand on it.

By this time, CalLite had already ceased operations, yet Southwest competitors continued to try to create new subsidiaries in their rival’s image. In October 1996, Delta debuted the Delta Express, a low-fare, point-to-point subsidiary designed to connect the Northeast and Midwest with Florida. The launch of Metrojet from US Airways followed in June 1998 trying to gain a stronger foothold in Baltimore.

Despite the difficulties of waging a war on multiple fronts, Southwest knew it had a long-term winner in its low-cost, high-frequency, mass-charm strategy.

Writing a note—this time, in light of Southwest’s defense of Baltimore, with allusions to the War of 1812—Herb asked his People to continue to see themselves as Freedom Fighters. “Just as against the United Shuttle,” he wrote, “the crucial elements for victory are the martial vigor, the dedication, the energy, the unity and the devotion to warm, hospitable, caring, and loving Customer Service of ALL of our People ALL of the time in every place on our system.”

Southwest’s People responded in kind—with even more kindness. Meanwhile, the competition struggled to keep pace with Southwest’s efficiencies. By 2000, according to the San Francisco Chronicle which cited a review of government records, two out of every three United Shuttle flights between Los Angeles and San Francisco were either more than 15 minutes late or canceled. A year later, in October 2001, the after-effects of the 9/11 terrorist attacks officially put the Shuttle out of business. Metrojet folded that same year, followed by Delta Express in 2002. Their demise proved in no uncertain terms that imitation does not a war plan or airline make—and that, as Herb stated in his taped address to Employees in 1994, Southwest possessed the “. . . tenacity and courage to prevail over any odds and over any competitor.”