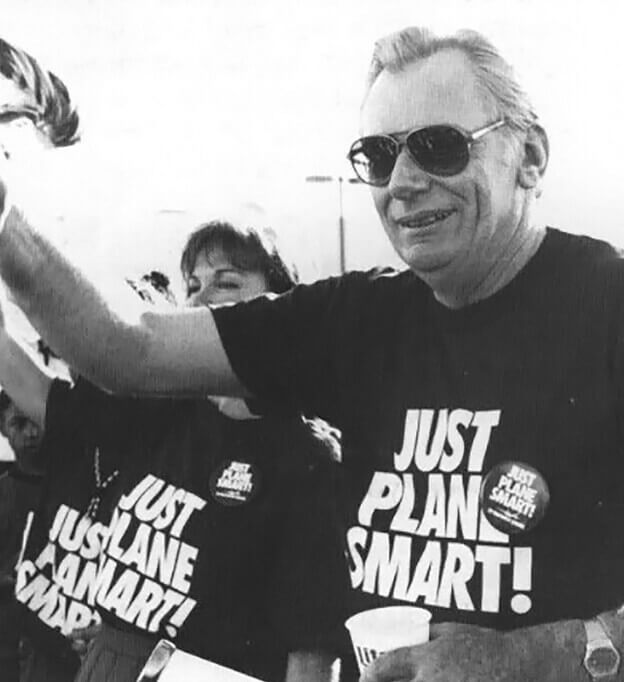

Herb and other Southwest Employees celebrate their new slogan, 1990.

Armed and Dangerous: The Malice in Dallas

What had begun as some gentle ribbing between Stevens Aviation Inc., a general aviation service center, and Southwest Airlines seemed to be escalating…quickly.

Earlier, word had reached Stevens’ offices in Greenville, South Carolina, that Southwest had adopted a new catchphrase: Just Plane Smart. A Stevens marketing exec noted how similar it was to its own “Plane Smart” slogan and scribbled a cheeky letter to Southwest CEO Herb Kelleher.

While most companies would settle the dispute the conventional way—by calling in the lawyers and burning through ungodly amounts of cash litigating it—the Stevens executive wondered if Southwest might be open to a lighthearted duel. The gutsy marketer suggested the companies’ respective CEOs settle things with a winner-take-all arm-wrestling competition—with the “victor” earning the rights to the slogan.

When Kurt Herwald, CEO of Stevens Aviation Inc., was informed of the letter, he didn’t bat an eyelash. He figured Herb—who was known to dress up as Elvis at public events or a leprechaun for St. Patrick’s Day—would enjoy the joke. But when the proposed showdown somehow made its way to the press, he decided to call Herb directly.

To Herwald’s surprise, the Southwest receptionist patched him right through.

As Herwald leapt into an explanation, Herb told him not to worry. Southwest had tipped off the press. Herb not only loved the idea, he promised to promote the hell out of it. “This is going to be cool,” he said. “We’ll have a blast doing this.”

Herb’s enthusiasm for the stunt, quickly christened “Malice in Dallas,” surprised no one in Marketing or PR, where Employees were used to Herb championing unorthodox ads and brand campaigns.

“Malice in Dallas” embodied many of the tenets that have made Southwest campaigns so beloved for so long. It defied conventional wisdom, championed individuality, and embodied the Fun-LUVing Attitude that’s always characterized Southwest Culture and Employees. As Herb was fond of saying, “We take our competition seriously, but not ourselves.”

At Southwest, the more deftly a campaign could model how its People should approach their work, the better. If Herb had the guts to cast aside his CEO status to make a crowd feel giddy for an hour or two, think of the license that gave Employees to make Customers feel loved.

Southwest chose the Dallas Sportatorium—a ramshackle old wrestling venue—to host the spectacle since it could easily fill its 4,500 seats with boisterous Southwest Employees. And in a move years ahead of its time, Southwest stoked public interest by producing a short faux documentary chronicling Herb training for the big match.

Aided by an enthusiastic group of Southwest Employees—including a class of new Flight Attendants—he progressed from struggling with sit-ups and jumping jacks to effortlessly curling oversized bottles of Wild Turkey and climbing a single stairwell without his knees locking up.

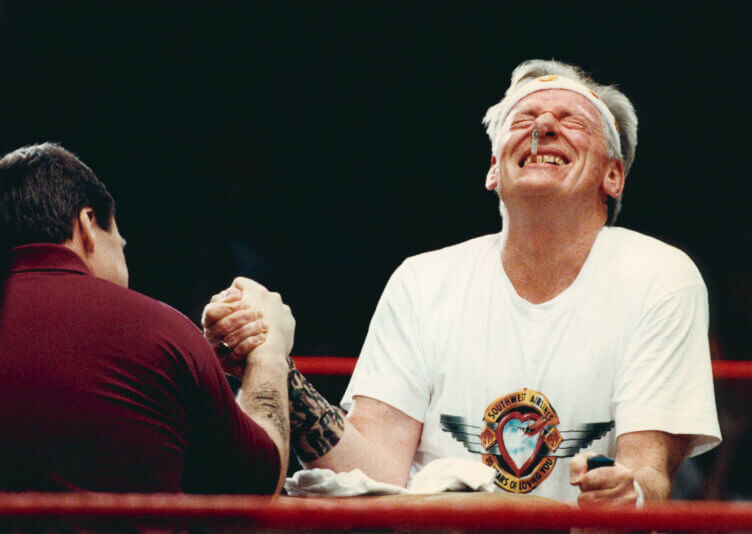

Herb struggles valiantly to hold off Kurt Herwald.

Behind the scenes, Herb and Herwald choreographed the event as if they were staging a real wrestling match. After a series of humorous preliminary bouts—Herb pinned by a diminutive young woman and Herwald barely losing to a former Texas arm-wrestling champion—the two men met for the main event, the result of which was prearranged.

Spectators who’d packed the Sportatorium on March 20, 1992, were in for a show. A red-robed “Killer Kurt” Herwald in a polo shirt, slacks, and sunglasses strode into the ring followed by toothpick-twirling “Smokin’ Herb” Kelleher, clad in sweatband, white bathrobe, and black boots. Taped on each boot was a pack of cigarettes, Southwest stickers, and an airline-sized bottle of whiskey. In a clever touch that underscored Southwest’s quick wit, Herb read from a declaration, which he claimed was authorized by no less than the Supreme Court of Texas, officially sanctioning the bout. It was time for the “wrastling” to begin.

When the final showdown arrived, Herb slowly rose from a recliner placed in his corner and locked his right hand with Herwald’s own. As the referee called for the competitors to place their left arms down, Herb’s face turned from supreme confidence to something approaching panic.

Reaching frantically with his left hand, which still held a cigarette, Herb pleaded with the referee for a quick bathroom break. Herwald momentarily loosened his grip.

He’d fallen right into Herb’s trap. As Herwald relaxed his arm, Herb put all of his strength into pinning Herwald’s arm before the referee could even react to the question.

After leaping around the ring, pumping his fists in exalted victory, Herb was told his win was null and void, as he’d broken the rules. Herb, feigning shock, yelled at the referee: “I didn’t know there were any rules!”

As their right hands clasped a second time, Herwald took an immediate lead, pulling Herb’s hand over the midline. For the next 20 seconds, they flexed and stretched—with, in Herb’s case, veins practically popping through his neck.

At one point, Herb appeared to bring Herwald’s arm back to the center, but it was merely a last-gasp push in a fight destined to go to the “better” man. Within seconds, Herb’s arm was pinned down hard, knuckles slammed to the table.

With peals of laughter still echoing through the hall, both CEOs announced they’d be making donations to their respective charities in honor of a hard-fought match.

Herb, ever the showman, gave the best part to Herwald, who disclosed he was allowing Southwest to continue to use its Just Plane Smart slogan. Herb praised his opponent’s selflessness before calling for a stretcher to carry him from the arena.

What may have surprised even Herb was how much media attention the event attracted. In addition to local newspaper, radio, and TV coverage, NBC Nightly News with Tom Brokaw aired an extended segment shortly after the event. President George H. W. Bush wrote Herb an effusive note. And praise from Employees and Customers flooded into Southwest offices.

Studies estimated that Southwest earned as much as $6 million in publicity as a result. And Herwald himself said that the event boosted the name recognition of Stevens Aviation so much that the company enjoyed 25 percent annual growth for the next four years.

Profiled repeatedly in PR textbooks “Malice in Dallas” shows what can be achieved when a company stays in character and remains authentic to its own spirit.

When Herb was asked after the event if it was a perfectly staged publicity coup, he wryly answered, “Why, I never even thought about it in those terms.” Thankfully, his customized black “Malice” boots have been preserved and enshrined in an exhibit at Southwest Headquarters in Dallas, offering proof that Herb got the last laugh after all.